13 Aug ANDREWS ESSENTIAL FIERY FOODS FACTS, THAT EVERY PYROGOURMANIAC NEEDS TO KNOW PART 62

ANDREW’S HISTORY OF SPICES

EARLY HISTORY

Recent discoveries have revealed that from as far back as 50,000 B.C. humans had used the special qualities of aromatic plants to help flavour their food. Primitive man would have utilized the sweet-smelling spices in order to make their food taste better. They would have offered up all sorts of aromatic herbs to their primitive gods. He would have used the spices to heal himself when he was ill. From that moment on, spices played an important role in human existence. Though the word “SPICE” didn’t appear until the end of the 12th century (a derivative of the Latin word “species,” which denoted a wide variety of products), the use of herbs dates back to early humans. Primitive peoples wrapped meat in the leaves of bushes, accidentally discovering that this enhanced the taste of the meat, as did certain nuts, seeds, berries–and even bark. The spice trade developed throughout the Middle East in around 2000 BC with Cinnamon and Pepper. Already in 3500 BC the ancient Egyptians consumed spices in the food, used them to manufacture cosmetics and embalm the dead. The Egyptians believed that the soul returns to the body of the deceased, and therefore the bodies of pharaohs and their wives and nobles were mummified and buried with all their wealth. In fact, the word spice comes from the same root as species, meaning kinds of goods. By 1000 BC China and India had a medical system based upon herbs. Early uses were connected with magic, medicine, religion, tradition, and preservation.

The ancient Indian epic of Ramayana mentions Cloves. It is known that the Romans had Cloves in the 1st century AD because Pliny the Elder spoke of them in his writings.

The first SPICE expeditions were organized in ancient times to ensure that these coveted commodities would always be in supply. Legend has it that around 1000 B.C. Queen Sheba visited King Solomon in Jerusalem to offer him “120 measures of gold, many spices, and precious stones.” A handful of Cardamom was worth as much as a poor man’s yearly wages, and many slaves were bought and sold for a few cups of Peppercorns.

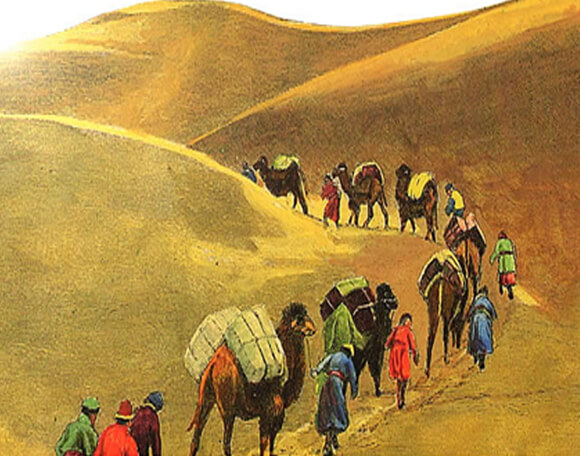

The story of Joseph, the owner of the Coat of many colours, is also linked to the spice trade. Envious brothers decided to kill him, but saw that “a caravan of Ishmaelites was coming from Gilead, with their camels bearing aromatic gum and balm and Myrrh, on their way to bring them down to Egypt.” The brothers sold Joseph for twenty pieces of silver, and returned to their father Jacob with Joseph’s bloody clothes. Jacob was heartbroken. And Joseph was bought by “an officer of Pharaoh” and eventually became a high-ranking court. Thanks to his ability to interpret dreams of Pharaoh, the country was saved from starvation. Later, Joseph got even with his brothers who had not recognized him, by selling them bread. Brothers brought him a gift of “a little balm and a little honey, gum, Myrrh, pistachio nuts, and almonds.”

Indonesian merchants went around China, India, the Middle East and the east coast of Africa. Arab merchants facilitated the routes through the Middle East and India. This made the city of Alexandria in Egypt the main trading centre for spices because of its port. The Arabs tried to keep in secret both the source of supply, and land routes to places full of spices. The classic route crossed the river Indus, went through Peshawar, Khyber Pass, on the territory of Afghanistan and Iran, and then turned south to the city of Babylon on the Euphrates River. Thence spices were brought to one of the cities that have achieved the greatest flourishing at the time. The most important discovery prior to the European spice trade were the monsoon winds (40 AD). Sailing from Eastern spice growers to Western European consumers gradually replaced the land-locked spice routes once facilitated by the Middle East Arab caravans.

Nearly 2,500 years ago, Arab traders told stories of the ferocious Cinnamon bird, or cinnamologus. This large bird made its nest from delicate Cinnamon sticks, the traders said. One way to get the Cinnamon was to bait the cinnamologus with large chunks of meat. The birds would fly down from their nests, snatch up the meat, and fly back. The precarious Cinnamon nests would collapse when the bird returned weighted with its catch. Then quick-witted traders could gather up the fallen Cinnamon and take it to market.

As enticing as the tale is, the fabled cinnamologus never existed. The story was most likely invented to ward off curious competitors from attempting to seek out the source of the spice. For many years, the ancient Greeks and Romans were fooled.

It is mentioned in 3 books that I was able to find-

PLINY THE ELDER [1st century CE] (Natural History, Book 10, 50): There is a bird of Arabia called the cinnamolgus which makes its nest out of Cinnamon twigs; the people of that country knock the birds down with lead-weighted arrows, and use them for trade.

ISIDORE OF SEVILLE [7th century CE] (Etymologies, Book 12, 7:23): The Cinnamologus is a bird from Arabia which gets its name from building nests from Cinnamon bushes. The nests are built high up on fragile branches so men cannot climb up to reach them. Since merchants favour this Cinnamon more than any other kind and pay high prices for it, men knock down the nests with leaded arrows.

BARTHOLOMAEUS ANGLICUS [13th century CE] (De proprietatibus rerum, book 17): Of Cannel and of Cassia men told fables in old time, that it is found in birds’ nests, and especially in the Phoenix’ nest. And may not be found, but what falleth by its own weight, or is smitten down with lead arrows. But these men do feign, to make things dear and of great price; but as the sooth meaneth, cannel groweth among the Trogodites in the little Ethiopia, and cometh by long space of the sea in ships to the haven of Gelenites. No man hath leave to gather thereof tofore the sun-rising, nor after the sun going down. And when it is gathered, the priest by measure dealeth the branches and taketh thereof a part; and so by space of time, merchants buy that other deal. (Mediaeval Lore from BARTHOLOMEW ANGLICUS (London, 1893/1905)

The Romans used the spices widely and extensively and the demand caused the need to find the way to India that would put an end to the Arab monopoly on the spice trade. Knowledge of weather phenomena, sea currents and monsoons contributed to the fact that soon the Roman ships laden with precious spices already committed voyages to Alexandria, the main Roman port in Egypt. The Romans were famous gourmets and fans of luxury: they consumed spices in meals, hung bunches of herbs in homes, used oils extracted from spices for baths and for keeping fire in the lamps. Wherever there were the Roman legions the use of spices and herbs was introduced, that’s how the spices first appeared in Northern Europe. The Fall of the Roman Empire in the V century and the beginning of Middle Ages marked a long period of stagnation in the culture, including the knowledge of spices.

The Prophet Muhammad, founder of Islam, married a rich widow of a spice merchant. Missionary zeal in spreading his faith in the territory of the East was inextricably linked with the spice trade. While Western Europe was dozing, this profitable business was quickly deploying in the East. Since 1000 AD and for the next three centuries the Crusaders brought from the East an appreciation of spices. In the fight between Christians and Muslims for supremacy in trade Venice and Genoa have become trading centres; ships sailing to the Holy Land with the Crusaders returned with a cargo of spices, silks and jewels. Due to the fact that the spices were a rare commodity, they were appreciated by the weight of silver and gold and soon the trade began to flourish again.

MIDDLE AGES

Spices were among the most luxurious products available in Europe in the Middle Ages, the most common being Black pepper, Cinnamon and Cassia the cheaper alternative, Cumin, Nutmeg, Ginger and Cloves. Clove was not found on a list of household spices before the Apici Excerpta by Vinidarius, which is a supplement to Apicius’ De Re Coquina, written probably around 6th century AD.

The first recipes with clove are those by Anthimus, Greek doctor of Frankish King Theuderic I, in Epistola de observatione ciborum (Epistle on food diet), which is a dietary text of the 6th century with recipes. Though most recipes by Anthimus are Roman indeed, we find more Ginger in them than in recipes by Apicius.

They were all imported from plantations in Asia and Africa, which made them extremely expensive. From the 8th until the 15th century, the Republic of Venice had the monopoly on spice trade with the Middle East, and along with it the neighbouring Italian city-states. The trade made the region phenomenally rich. It has been estimated that around 1,000 tonnes of Pepper and 1,000 tonnes of the other common spices were imported into Western Europe each year during the Late Middle Ages. The value of these goods was the equivalent of a yearly supply of grain for 1.5 million people.

Looking at medieval world maps that attempt to incorporate information about Asia from the Book of Genesis, legends of the conquests of Alexander, Christian prophetic literature, especially regarding the apocalypse, and real and fabricated travel accounts such as those of MARCO POLO and JOHN MANDEVILLE.

MARCO POLO was born in 1256 in the family of jewellery dealers, enthralled by the wonders of the East. They travelled as far as China, stayed at the imperial court of Mongol Great Khan, and during that trip which lasted twenty-four years MARCO has travelled the whole of China, Asia and India. He told about it in his Book of the Marvels of the World, also known as The Travels of Marco Polo, written on pieces of parchment while in custody after a sea battle between Genoa and Venice. In his book MARCO POLO mentioned that during his travels he saw how spices grow and he dispelled the terrible legends and rumours, which were spread by Arab traders before. The traveller brought poetic descriptions of Java: “… The island abounds in wealth. Pepper, Nutmeg…, Cloves and all other valuable spices and herbs are the fruits of the island, thanks to which it is visited by so many ships loaded with goods, bringing huge profits to owners.” His book has inspired the next generation of seafarers and explorers who wanted to make a fortune and glorify their names.

The MAJOR SPICES, mainly Pepper, Ginger and Cinnamon, are distinguished from the MINOR SPICES of lesser use, depending on the time, the country or the book under consideration. Consumption of spices varies according to fashion, price and social status. The King of France Jean le Bon for instance, in the 14th century, bought more Cinnamon flowers, a very expensive minor spice, than Cinnamon which was a major spice five times less expensive. At the court of Burgundy, in the 15th century, long Pepper and Grains of Paradise replaced the then common Black Pepper, though the gentry stayed fond of Black Pepper. In the 14th century, in France, the least expensive spice was Pepper. In the 15th century, Ginger was the least expensive, and Saffron, because its price had become prohibitive, almost disappeared altogether from the table of the Lords.

People in the Renaissance found many uses for spices. Pepper and other spices sifted through the fibre of Renaissance living. The spice trade was basic to the Renaissance economy.

The fascinating history of spices is a story of adventure, exploration, conquest and fierce naval rivalry. The people of those times used spices, as we do today, to enhance or vary the flavours of their foods. Spices were also flavour disguisers, masking the taste of the otherwise tasteless food that was nutritious, but if unspiced, had to be thrown away.

The role of the capital of spices, which had been so cherished by Venice in the past, moved to Lisbon. But before, CHRISTOPHER COLUMBUS had chosen a new route to travel to the East, he sailed west. In 1492, according to his ideas, he reached the shores of Japan, but in fact he discovered San Salvador, now called Watling Island, one of the islands near the Bahamas, Haiti and Cuba. Columbus discovered the New World and became the first Westerner who experienced the fiery taste of Chilli. Going to the second voyage, Columbus left Spain accompanied by fifteen hundred people to establish Spanish rule in the New World, where he hoped to find gold and oriental spices. But instead he found scented Jamaican Chilli and Vanilla and brought potatoes, cocoa, corn, peanut and turkeys from South America to Europe.

It is often assumed that prohibitive prices for spices during the Middles Ages kept them to the fortunate few of the times. But in fact, the study of the period between 1345 and 1347 of the books of BARTHOLOMEW BONIS, a rich 14th century merchant of Montauban, who dealt in spices among other things, shows that the consumption of spices was more important than we might expect, for such a small provincial town of the south of France:

Pepper, Saffron, Ginger, Cinnamon and Cloves were the most bought spices, in decreasing order, and there was also dried Coriander, as a matter of interest. In the spice mixes for PIMEN, the ancestor of HIPPOCRAS, there was also Grains of Paradise, Spic Nard, Nutmeg, Mace, Cubeb, long Pepper, Galangal and Zedoary

These spices were bought either as medicine, but only with a with a prescription, or for cooking or making PIMEN. The spices for cooking or making PIMEN were bought mostly for feasts, like Christmas, marriages or engagement parties. The hosting of renowned visitors would also favour purchases of candied Ginger.

Buyers of spices, apart from the poorest, came from all social categories, Notables, lords, bourgeois, but also craftsmen like butchers, cobblers, tailors, bakers, carpenters, blacksmiths and even herdsmen and ploughmen.

The spices from the East were valuable in those times, during these Middle Ages, a kilo of Ginger was worth 2 sheep, a kilo of mace worth 6 sheep or 1 cow. Pepper, the most valuable spice of all, was counted out in individual Peppercorns, and a sack of Pepper was said to be worth a man’s life. DA GAMA’S Famous historical voyage intensified an international power struggle for control over the spice trade.

The most lucrative of the spice traders during this time were the Arabians. Southern Arabia was the great spice emporium in antiquity The Arabs used mythological stories to succeed in acquiring the first monopoly on the spice trade. The period between the 16th to the 18th century saw the English explore and control the spice trade. After this period, the Americans also entered into the spice trading community. Thus, one can see that the history of spice has always been a history of control, of power and of wealth. Spice has proved to be the number one commodity of trade that has made a lot of difference in the lives of many people – especially in the way we eat food – simply because it just tastes better with a little bit of spice!

More than 100 medieval cookbooks survive today. In the Libre del Coch of Master Robert, written for the king of Naples, are about 200 recipes, 154 of which call for Sugar, 125 require Cinnamon, 76 Ginger, and 54 Saffron. Spices ordered for the wedding of GEORGE “THE RICH,” DUKE OF BAVARIA, and JADWIGA OF POLAND in 1475 included 386 pounds of Pepper, 286 pounds of Ginger, 257 pounds of Saffron, 205 pounds of Cinnamon, pounds of Cloves, and 85 pounds of Nutmeg. Clearly, recipes from the era called for not only large quantities of spices, but also a great variety. Spices such as Cinnamon or Nutmeg associated with desserts were used in meat and fish dishes. Sugar functioned as a spice during the era. Styles in cooking change, and given the modern preference for spicy dishes, we can appreciate the medieval culinary aesthethic that emphasized colour, ingenuity and a high degree of processing. Far from the idea of simply grilling meat, medieval food required chopping, molding, simmering and various steps including sauces or aspic. It has often, wrongly, been said that medieval cooks used plenty of spices to cover up the taste of meat gone bad. But was it simply because we now know how to preserve meat, that the use of spices saw a drastic reduction, from the 17th century on.

Actually, medieval cooks knew well how to use spices, how to measure them out and combine them with bread based liaison and the acid tasting products such as vinegar or verjuice which is a delicate balance often forgotten by modern chefs.

INDIAN SPICE TRAIL

The fame of Indian spices is older than the recorded history. The story of Indian spices is more than 7000 years old. Centuries before Greece and Rome had been discovered, sailing ships were carrying Indian spices, perfumes and textiles to Mesopotamia, Arabia and Egypt. It was the lure of these that brought many seafarers to the shores of India.

Long before Christian era, the Greek merchants scoured the markets of South India, buying many expensive items amongst which spices were one. Epicurean Romans were spending a fortune on Indian spices, silks, brocades, Dhaka muslin and cloth of gold, etc. It is believed that the Parthian wars were fought by Rome largely to keep open the trade route to India. It is also said that Indian spices and her famed products were the main lure for crusades and expeditions to the East.

In 1497, VASCO DA GAMA set sail on a journey to the Orient on orders from Dom Manuel I de Portugal, the king of Portugal at the time. He wanted the Portuguese explorer to find a seafaring passage to India in order to cut out the middlemen in the Mediterranean who had exclusive control on the spice trade. What DA GAMA found was a direct path to the city of Calicut, also known as “The City of Spices”, once he sailed down the west coast of Africa, around the Cape of Good Hope, back up the eastern border and across the Indian Ocean. This meant that Portuguese hands got a firm hold on the spice trade and helped make Portugal the wealthy superpower that it was known for throughout the Age of Discovery. Under the guise of the spice trade, Portugal expanded territorially and commercially. By the year 1511, the Portuguese were in control of the spice trade of the Malabar coast of India and Sri Lanka. Until the end of the 16th century, their monopoly on the spice trade to India was exceptionally profitable for the Portuguese. The main product brought back to Lisbon was Black Pepper. Piper nigrum (Black Pepper) was as valuable as gold in the age of discovery. In the 16th century, over half of Portugal’s state revenue came from West African gold and Indian Pepper and other spices. The proportion of the spices greatly outweighing the proportion of gold. Probably because they had the most ambitious explorers, most notably a guy named AFONSO DE ALBUQUERQUE, who, incidentally, is the namesake of an especially delicious mango, the Alphonso.

In the meantime, SIR FRANCIS DRAKE made a circumnavigation, sailing his ship “Golden Hind” through the Strait of Magellan and the Pacific Ocean to the Spice Islands. These islands attracted attention all over Europe. Each nation sought a monopoly on the spice trade, which, as it was known, was a source of immense riches. The Dutch have solved that problem in their own way, they imposed restrictions on the cultivation of Nutmeg and Cloves outside the islands of Ambon and Banda (Moluccas). But their efforts were nullified by the French missionary PIERRE POIVRE who discovered these types of plants on the next island, where the seeds were brought by birds, and delivered them to Mauritius. They began to cultivate cloves on Zanzibar, which is still the largest producer of this spice, and Nutmeg on Grenada, an island in the West Indies, which is also called the Nutmeg Island. Around the same time, the British conducted experiments on the cultivation of nutmeg and cloves in Penang; later they began to cultivate spices in Singapore by the order of Sir Stamford Raffles, the famous representative of the East India Company and the founder of Singapore.

For three centuries afterwards the nations of Western Europe-Portugal, Spain, France, Holland, and Great Britain fought bloody sea-wars over the spice-producing colonies. Trade in India in the present day involves less nationalistic qualities than it did in the past. Spice growers now export their products through their own organizations or through exporting houses. Spices are now distributed by food manufacturers, wholesalers and retailers.

In the 17th century, the Dutch became power players in the spice trade when the various provinces of the Netherlands united their trading ventures to form the DUTCH EAST INDIA COMPANY. Their centre in the “spice islands” of Southeast Asia was called Batavia, present-day Jakarta. The penalty for stealing spices in the Dutch empire was death.

The Dutch ruled the market with a rod of iron. If the price of Cinnamon fell too low in Amsterdam, they burned the spice. They soaked their Nutmegs in milk of Lime, a process which did not affect flavour, but supposedly killed the germ of the nut. This was to prevent nutmegs from being planted elsewhere.

France’s role in spice trading was generally a minor one, not backed by its government. However, they helped destroy the century-old Dutch spice monopoly when, in 1770, the French contrived to “kidnap” enough Cloves, Cinnamon and Nutmeg plants from Dutch possessions to begin spice-growing in the French islands of Reunion, Mauritius and Seychelles in the Indian Ocean and in French Guiana on the north coast of South America.

AMERICA WANTS IN

In the late 18th and 19th centuries, Americans became directly involved in the spice business as the sleek clipper ships of New England began to dominate world trade. So many Pepper voyages were undertaken from New England to Sumatra that the price of Pepper dropped to less than three cents a half kilo in 1843, a disastrous slump that affected many aspects of American business.

The leader of the American spice trade was a sea captain named JONATHAN CARNES. Sailing on one of the early American trading voyages out of Salem in 1778, he discovered places in the Orient, principally in Sumatra, where he could deal directly with the natives, thus circumventing the Dutch monopoly. Financially backed by a wealthy Salem family, he made a voyage in 1795 which yielded 700% profit in spices. This sent America into the spice competition so actively that between 1784 and 1873, about a thousand vessels made the 24,000 mile-long trip to Sumatra and back. In 1818, when the Pepper trade was particularly intense, 35 vessels made the long and dangerous trip. Pepper trade furnished a great part of the import duties collected in Salem (which at one point were enough to pay 5% of expenses of the entire U.S. government). Pirates finally put America out of the oriental trade. American merchant ships were raided and destroyed time and again, and the United States government decided against backing the spice trade with naval protection in foreign waters.

Ultimately the New England spice trade fell off sharply when piracy in the Java and China Seas made long voyages for Pepper too dangerous. Meanwhile, the American spice business, like the rest of the country, was moving west. In 1835, American settlers in Texas developed Chilli powder by combining various ground red Chillies from Mexico, thus adding new dimensions to American taste. Later, once the gold rush had subsided, herbs were grown commercially in California. Mustard seed was grown in North Dakota, Montana, and Canada’s prairie provinces.

Throughout history, the country that has controlled the spice trade has been the richest and most powerful in the world. Fortunately, these aromatic plants are not so costly today as they once were. In the 19th Century Great Britain’s maritime prowess gradually established her as the leader of the spice trade, and London’s Mincing Lane became the spice-trading centre of the world.

THE STORY OF SPICE MIXES: WHAT MAKES SOME DISHES SO HARD TO RESIST

Each time I make my spice blend for Bharwan Bhindi,( stuffed Okra), I get the same reaction: Apprentice chefs, assigned to help me with the prep, seemingly look on in bewilderment and dare I say awe, as I blend together Fennel and Amchur and more common spices, tasting to see whether the proportions have mixed well enough to replicate the taste of my home. Like other home cooks, no one in my family cooks by using precise measurements, including myself. The proportions of spices that go into the “mix” are driven by individual discretion and palate. When we seek a balance, it is to try and recreate taste from memory.

For the longest while, I would be amused at other chefs’ perplexity and inability to make masala’s and spiceblends in my absence. It’s not rocket science after all. Just a handful of spices go into the mixes and considering that most chefs I know tend to cook with andaaz and an instinctive knowledge of balancing flavours, why should it be seen as a semi-mystical task to assemble Spiceblends? It later dawned on me that it had to do with the memory of taste. All of us have different ones, having grown up with different cultures eating different kinds of foods. And to successfully replicate flavours of a particular culture, you must have sufficient prior exposure to that Culture’s food traditions. Trainee chefs, obviously, could not therefore be expected to make my ETHIOPIAN BERBERE or my RASTAMAN DRY JERK RUB blends, I use in the food I personally love to eat in quite the same way as I do .And that is also the reason behind the proliferation of different readymade Spice Rubs and Blends all over the country.

THE TRADITION OF SPICE MIXES

While we can now buy BLENDS & RUBS off supermarket shelves, Farmer’s Markets, Chilli Festivals, paying little attention to the individual spices in their BLENDS & RUBS, it is important to remember how the tradition of these spice mixes really started – as individualistic expressions of the art of balancing flavours. Each person and each household had different flavours, and certainly different mix of flavours they favoured. The spice mixes that we take so much for granted also differed slightly, according to the different palates and adventurous balancing of the taste. There were no generic mixes. And there was also no awe associated with many of these. Each home simply had its own recipes.

As Chefs, Cooks, Spice blenders and other Masala makers started making these spice powders for retail, the reputation of specific brands spread according to how much they were preferred and accepted by their patrons. If the CHAATWALLAHS of old Delhi boast about their secret kala Chaat masala with many different types of spices, it is merely because of the large number of patrons who started validating that particular flavour. Some of the best home-made chaat from Uttar Pradesh is made with nothing more elaborate than roasted Cumin, Amchur powder and Black rock Salt, the most basic of chaat masalas. When Exotic bazaar-bought chaat masalas boast 100 ingredients in the spice mixes, it is also to flavour their reputations. Merely a smart case of marketing.

SPICES IN KEBABS

For a very long time, the holy grail of Indian chefs in restaurant kitchens had been to decipher the Masala for Galouti Kebab. For someone like me, who grew up in Kingscliff, this seemed almost impossible in the beginning. The Kebabs I made in my home were quite relatively simply spiced. Instead of a readymade “MASALA”, we made our own SPICEBLENDS, where whole spices like Brown and Green Cardamom, Cinnamon, Bay leaves, Black Peppercorns, Cumin, Nutmeg, Mace and Cloves would be tied in a muslin cloth and put into the Keema curry to boil and cook, providing ample aromatics. The Galouti Kebab was initially just an improvisation on this basic kebab recipe, where the meat was made more tender using raw papaya as tenderiser.

Cooks in the Indian Awadhi court, because they were feeding the rich and the powerful, started adding more elaborate MASALAS to their kebabs. Many of these were essentially fragrant ingredients like khus ki jad (Vetiver roots) and paan ki jad (Galangal). Others were ingredients and herbs used in Ayurveda and Unani medicine, some ostensibly aphrodisiacs, others said to improve vitality, strength, complexion etc. Many of these ingredients were quite exclusive, hard to come by and certainly not available into regular Australian home kitchens at the time. But because the Awadhi banquet chefs began catering to an elite English audience, much like today’s foie-gras seekers who sought the expensive and hard-to-come-by devine blessings more and more elaborate Spice Blends seem to have been concocted, regardless of the fact that you can scarcely taste all the ingredients in them. Some of these BLENDS & RUBS were reputed to contain over 100 spices. Given the miniscule quantities used for all the different spices and herbs, it is safe to bet that the omission of at least a dozen would make no difference to the final taste of the preparation!

WHAT REALLY ARE THE COMPOSITION OF BLENDS & RUBS?

To decipher this is still to this day the holy grail of many chefs. It may be as futile an exercise too. Because you don’t really need ingredients like shilajeet and others, used in desi medicines, and many in the grey area as far as their culinary use goes, to make perfectly great Galoutis Masala. It just has to do with your instinct for balancing flavours, your memory of taste and your acquaintance with other cultures food.

RARE SPICES SELDOM SEEN IN ENGLISH SPEAKING KITCHENS

There are some less commonly known available spices with strong aromas and flavours that can certainly add to the regional recipes you are cooking.

Here’s my pick of single SPICES & SPICEBLENDS and what to do with them:

KEBABCHINI

This is similar to Pimento (dried berry of the Caribbean Pimento tree) but is really cubeb (cultivated in south-east Asia, sometimes called Java Pepper). This one looks like Pepper but has a tail attached. Cubeb was used by Arabs and the Arabian Nights mention this as a cure for infertility (in Unani medicine, it is also used to heighten sexual pleasure while in Ayurveda, it was used as a mouthwash). In India, this came through trade with the Chinese, hence the suffix “chini”. This is a strong spice and best used in meat curries and kebabs for a strong aroma.

KALPASI/DAGADH (BLACK STONE FLOWER)

It is a southern spice. A moss-like substance that grows on wet stones, this is used in Tamil cooking to flavour meat curries. It is also an essential ingredient in the Goda Masala and gives it that strong smell. But by far its most “exotic” use has been in Hyderabadi cooking where it goes into kebabs and biryani mixes.

PIPPALI (LONG PEPPER)

It tastes pungent and sweet at the same time. This is one of the oldest ingredients of Indian cooking that have almost disappeared. Chilli, as we all know, came with Colonial trade into the Subcontinent. It was gradually to replace most other spices providing pungency to a dish. Pippali along with Pepper were the original spices of India that were used to flavour food before the advent of Chillies.

SAFFRON

The most expensive spice in the world because it requires a lot of work to grow. It comes from the stigma of the blue flowering crocus, CROCUS SATIVUS, and it must be handpicked. About 200-500 stigmas make up a single gram of Saffron, and usually there are only three per flower. It takes acres upon acres of land to grow enough flowers to even produce a Kilo of this spice. It’s a good thing that most recipes only call for a pinch of it then, since only a small amount is required to give food both beautiful colour and an exotic flavouring. Saffron is used in paella, sauces, rice, seafood dishes, as well as many other foods from many cuisines all over the world.

AMCHUR POWDER

Made from unripe mangos that have been sliced, sun dried, and then ground into a fine powder, Amchur powder is a commonly used souring agent in North Indian cooking. It is frequently found in curries, chutneys, stews, soups, and in vegetable dishes.

ASAFOETIDA

Asafoetida is an incredibly powerfully smelling spice that is used mostly in Indian vegetarian cooking. It is a good replacement for Onion and Garlic and is used in a lot of diets that are popularized in America. Some people who are eating gluten free gravitate toward this spice, which comes from the dried and powdered gum resin from several species of Ferula, a perennial herb.

AJWAIN

You may encounter this spice with the name Ajowan Caraway, Carom Seeds or Bishops Weed. It has a stronger flavour than Thyme or Caraway seeds, which it tastes like. Ajwain is used in small quantities and it is typically only used after it has been dry roasted or fried in ghee or oil. It belongs to the Apiaceae family along with coriander and cumin and is found in Indian and Pakistani cooking.

ANARDANA

Anardana is the dried seed of various wild pomegranate plants that has a sour and slightly fruity flavour. It works well in dry seasoning fish or as an ingredient in a marinade to season meats. Venison is exceptionally delicious when paired with Anardana. It is also a common ingredient in chutney and is popular in Indian cooking.

GALANGAL

Galangal, also known as Garingal in some medieval recipes, is a plant with an edible rhizome root, like Ginger and is native to Indonesia and China.

The consumption of Garangal developed starting in the 14th century in Europe, but it is already found in the spices bought by the Corbie monastery, in the 9th century: 10 lbs Garingal, Clove and Rostus root, which was native to India and of wide use in Roman cooking.

NIGELLA SEED

Fennel flower is another name for this spice. It has a pungent and slightly bitter flavour with a hint of sweetness and a body that is small, black, sharply pointed. This seed is commonly used in Bengali cooking.

GRAINS OF PARADISE

Grains of Paradise, also called Melegueta Pepper or Guinea Pepper, was often graine in French manuscripts, grayne or greyn of Paris in the English ones. In Catalan it was Nous de Xarch.

Melegueta comes from a Hindi word meaning Pepper.

The plant is native to Liberia and Ghana. It is a perennial plant with rhizomes, of the same family as Ginger. The dried seeds of the fruit are the Grains of Paradise. They were more appreciated in the medieval gastronomy of 14th and 15th century France than in that of the other European countries. It appears that the reference to Paradise in its name was part of this spice’s success. But its use declined, starting in the 16th century, when its African origins became known. It has practically disappeared from the shelves of the today’s supermarkets. It is still prized in Northern Africa in some spice mixes for Tajines dishes or some blends of RAS EL HANOUT. It is starting to be rediscovered now.

TASMANIAN PEPPERBERRY

This spice is used primarily in Australia’s bushfood, which are foods from local cuisines that have gained mainstream popularity in recent years. These dishes are usually made with ingredients that are indigenous to Australia, hence the popularity of the Tasmanian Pepperberry. This spice tastes slightly sweet, then gets spicier as the day goes on.

GREEN CARDAMOM

Native to Kerala in India, Cardamom is the fruit of a plant with rhizomes of the same family as Ginger. There are several sorts of Cardamom, Green cardamom which is the most used in cooking, White Cardamom, used in Indian pastries and Black Cardamom, adapted for heavily spiced dishes because of its strong camphor flavour. It eases digestion. It was also said to have aphrodisiac properties.

SUMAC

Sumac consists of the dried berries of a Mediterranean shrub, Rhus coriaria or Tanner’s Sumac, which is cultivated in Sicily, the south of Italy and throughout the Middle East. Sumac is supposed to have been used in Ancient Roman cookery, it is not found in Apicius. It is a spice commonly used today in Middle Eastern cooking in the cuisines of Lebanon, Syria, Turkey, Armenia, Iran, in which they give an acidic flavour to salads, fish or meat dishes. People can easily find them in Australian supermarkets.

During the Middle Ages, there was often Sumac in recipes of the Baghdad cookery book and I have found Sumac again in the Liber de coquina: II.10 De sumachia (Sumac), II.11 Recipe pullos (chicken) and V.11 De composito lumbardico (Lombard mix).

Were I Chinese, I’d have a largely different array of spices on hand to throw into my dishes as they sizzled away in a wok

When I’m at my house in Queensland, I call on more herbs than spices.

But since I like to cook the specialties of many countries, it’s impractical for me to buy the dozens of individual spices that comprise the flavour spectrum of each culture in quantities, my Chufa flour (an edible tuber, cultivated in some marshy regions of Spain and Italy, roasted and made into flour) might be used just once or twice a year, and otherwise grow stale.

So SPICEBLENDS & RUBS are the way to go, and the premixed ones are perfectly good (We actually make them and sell them commercially), though with the caveat that spices gradually lose flavour as they get older. Thus, they should be used as soon as possible after they are ground or pulverised. I keep quite an ensemble of renowned spice mixes in my cupboard – more mixes than individual spices. But saying that I couldn’t possibly live without Salt, pepper, Smoked paprika, Cinnamon, Chilli Flakes and Fresh Garlic & Ginger. I make my own SPICEBLENDS & RUBS, I even have my own personal recipe for falafel spice with over 18 components.

But, I’m interested in SPICEBLENDS & RUBS with tradition behind them. I want to know the story behind what I eat. So I decided to go around the world in SPICEBLENDS & RUBS, to learn what comprises each of the ones I use most often, and what traditions they hail from.

WHEN DEMAND RISES, IT OPENS THE DOOR TO AS MANY CHALLENGES AS IT DOES OPPORTUNITIES.

New technology is being used to find innovative ways to make the spice trade more transparent, in a market increasingly concerned with quality and provenance.

Spices are incredibly high-value commodities for ingredients they trade for huge amounts of money. Often, with such a high-value commodity, a massive amount of cheating goes on.

That cheating can take different forms. Unscrupulous traders find many ways to cut the spice, adulterating it with a bulking agent or blending with something else. It’s just general non-edible rubbish. Adding something of low or no value could boost the spice by a volume of 20-30%.

Another common cheat is to spike the spice with substances that give the impression of higher quality, such as food dyes to make the product take on a richer, more appealing colour. Sometimes these are industrial dyes, not intended for human consumption. There are hundreds of cases each year of valuable spices like Paprika and Saffron being found to be tainted with unauthorised harmful substances such as the dyes like Sudan I and Para red.

It’s hard to document the scale of cheating in the spice industry. But looking at the high-value herb Oregano, up to 40% of batches were fake.

But food-fraud detection is catching up with the cheats. Each spice has a “molecular fingerprint” that can be analysed using infrared spectroscopy. The fingerprint is made up of several thousand different molecules that are present in characteristic proportions. Any bulking agent or other additive will show up as an anomaly in the fingerprint.

Traditionally, samples would be shipped from a factory or shop to a laboratory. But it can take around two weeks from sampling to give results. In a supply chain, two weeks is a lifetime. That spice can be in 56 different countries by then.

Scanners that can be fitted to a smartphone are one solution labs are trialling. This way, a quick scan of the powder in front of you can give a green light to assure authenticity, or a red light to show that something is amiss.

A lot of spice companies are interested. They want to show that they don’t have any cheating going on. So If they can adopt the technology they can add a premium to their product, to show it has been scientifically tested to be pure.

In many ways, the history of globalisation is played out in the story of spices. From tightly controlled origins, the international spice trade unrolled along routes by land and sea to connect much of the world. Today, there is barely a country in the world where spices are not readily accessible.

Both India and the Caribbean islands have done considerable research on alternative uses for spices. The Indonesian government, through agencies like the Indonesian Pepper Exporters Association (AELI), could work with these countries to understand developments in spice usages, as well as improvements in cultivation techniques and plant material. Although some countries may cultivate competitive products, limited collaboration may help to grow the entire spice category worldwide, thus benefiting all involved.

It’s a really symbolic trade in the supply chain, because of the connections between different producing and consuming countries. It’s also a symbol of cultural globalisation, because we now consider spices quite ordinary in the west, when we didn’t use to. I can’t imagine Australia going without Mexican, Thai, Chinese or a good Indian curry.

The process was not always smooth, particularly in terms of its cultural impact. In its early days, the spice trade led to bloodshed and conflict, as well as bringing wealth. One hard to ignore legacy of the spice trade is colonialism. The search for a direct route, cutting out the middlemen, to find the source of spices stimulated European voyages that turned into colonial conquests.

Turning to the future, the spice trade has many new hurdles to overcome. Adapting and becoming resilient to climate change is likely to be crucial, if the trade is to remain sustainable while keeping up with the ever-growing demand for spices. This will be no mean feat, as their uses in food, health and wellness continue to evolve.

Spices allow you to be creative and adventurous with your cooking and best of all, they prevent you from eating another bland meal.

The demand for spices shows no sign of slowing up, as new industries are sprouting up to make use of spices in ways that go beyond flavouring food. In regions such as Europe and North America, new habits are changing the way we think about and consume spices.

CINNAMON

There are several varieties of trees in what botanists call the “ CINNAMOMUM ” family. Most of the Cinnamon used in the U.S. is derived from trees of the “ CINNAMOMUM Cassia” division of the family, which is why Cinnamon is sometimes referred to as Cassia. Among spice experts, this term is used to distinguish between the Cassia types of Cinnamon and the Sri Lankan type of Cinnamon. The cassia group is native to China, Indo-China and Indonesia. They produce the product most Americans recognize as Cinnamon, a reddish brown powder with a strong characteristic aroma and flavour. Quite different from these are the Ceylon and Ceylon-types of Cinnamon. The products in this case are characteristically tan-coloured, with flavour and aroma much milder than that of Cassia that the average person in the U.S. would consider them weak or poor Cinnamon. Most Sri Lankan Cinnamon brought into the U.S. is re-exported to Mexico, where it is preferred for certain confections. In labelling, however, bark from the CINNAMOMUM family (whether Cassia or Sri Lankan-type) may be called “cinnamon.”

The most commonly used Cinnamon in the U.S. comes from the Cassia type of cinnamon trees, for which there are three main producing areas. Indonesia supplies two types: “Korintje” and “Vera” or “Batavia”. China, now that the U.S. has resumed trade with that country, is an increasingly important source. Vietnam is the third producing area, (known for “Saigon” Cinnamon).

Indonesian Cinnamons (Cassia) come from the mountainous areas inland from the port of Padang on the island of Sumatra. The highest concentrations of essential oil in Korintje and Vera are found in the thicker bark on the lower parts of the trees. The grade designations for both Cinnamons are “Quality A”: (quills must be one meter long, taken from the main trunk), “Quality B”: (from the side branches) and “Quality C”: (broken pieces). Coming from a higher altitude, the Korintje Cinnamon characteristically has a slightly more intensive colour and flavour than the Vera and is thus rated the better type. In general, Korintje is deep reddish brown and has a sharp Cinnamon flavour; the Vera is lighter in colour.

NUTMEG AND MACE

Nutmeg is the seed of the Pala fruit tree, found close to the sea in well-drained areas of some tropical islands. The seed is partially covered by a thin red membrane that when removed and dried becomes the spice called Mace. Both are enclosed within a hard shell inside the fruit. Indonesian Nutmeg and Mace are grown on the islands of Sian and northern Sulawesi, and the processing centre is in Menado. Smaller amounts are grown in Maluku, Aceh, West Java, Irian Jaya, and West Sumatra. Most of the East Indian product today arrives in the U.S. cracked and cleaned, ready to be ground, whole Nutmegs cannot be fed directly into a grinding system as they are too hard. Indonesian Nutmeg is highly aromatic, with a distinctively characteristic bouquet. It tests high in steam volatile oil, but not as high as the West Indian in fixed oils, making it an excellent choice for grinding and use in the ground form.

About 12,000 tons of Nutmeg and Mace are traded annually, with the United States as the largest single importing market. Recently, the price of Nutmeg has soared from Rp 2500 to Rp 140,000 per kilo, due to a resurgence in global demand for the spice, combined with the weaker rupiah. Consumption is generally steady in the United States but rises in October through December as seasonal usage comes into play. New uses, such as aromatherapy oils, perfumes, and essential oils used as food flavourings may help to boost demand.

PEPPER

In terms of both volume and value, Pepper ranks as the main spice in international trade. Historically, Pepper has been one of the most sought after spices of the Orient, and the island of Sumatra produced a considerable supply. Pepper was valuable not only for its ability to flavour food, but also for its preservative qualities. In 1805, Indonesian Pepper exports reached a level of 7 million pounds; in 1997 the U.S. imported 41,602 tons of whole black Peppercorns. Of this, India supplied 44% and Indonesia 41%. The U.S. is the largest market for pepper, accounting for 25% of world trade. Total would trade amounts to $564 million or 140, 000 tons.

Pepper in Indonesia is principally grown on the island of Sumatra, a major producer of fine quality Black Pepper. Cultivation is centred in the Lampong district of south-eastern Sumatra and shipments are made from the port of Pandjang. This Pepper compares with pungency and flavour, testing high in steam volatile oil and non-volatile extract. Pepper is commonly intercropped with other cash crops, such as Coffee and Tobacco. Although the income per hectare is higher for perennial plants such as Pepper, it takes many years before these plants bear fruit. Farmers have to wait five years before they begin to harvest. Pepper also requires a large initial investment in seedlings, supports, and fences, plus the opportunity cost of a perennial crop with delayed yielding.

Pepper demand has experienced steady growth of about 4% in the past several years. Increased purchasing power throughout the 1980s in some Middle East and North African countries gave rise to sharp increases in pepper consumption. The U.S.’ demand has also risen, from 60.5 million pounds in 1985 to 78.5 million pounds in 1995.

The huge working capital needed at the farmer level weakened the purchasing power of exporters and forced many of them out of business. Those farmers who have maintained production are gaining substantially, earning Rp 43,000 ($7.50) per kilogram versus Rp 5000 ($3.50) a year ago.

CUMIN

Cumin is the dried seed of the herb Cuminum cyminum, a member of the parsley family. Used since ancient times, Cumin seeds were excavated at the Syrian site Tell ed-Der, which dates to the second millennium BC. In ancient Egypt, Cumin was used as a spice and also a preservative during mummification.

Originally cultivated in the Mediterranean, Cumin is mentioned in both the Old and New Testaments of the Christian Bible. What’s more, the ancient Greeks kept Cumin in a container on their tabletops, the same way Pepper is kept today. Used as toasted whole seeds or ground into powder, it’s grown throughout northern Africa, the Middle East, Central Asia and Mexico.

BIOACTIVES OF SPICES

Spices are a storehouse of many chemically active compounds that impart flavour, fragrance and piquancy. Spices recognized as several health benefits including lowers cholesterol. Most spices owe their flavouring properties to volatile oils and in some cases, to fixed oils and a small amount of resin which are known as oleoresins. Phytochemicals in spices are secondary metabolites, which are originated for the protection from herbivorous insects, vertebrates, fungi, pathogen and parasites . Most probably, no single compound is responsible for flavours but a blend of different compounds such as alcohols, phenols, esters, terpenes, organic acids, resins, alkaloids and sulphur containing compounds in various proportions produce the flavours .

There are also many healthcare benefits associated with spices; they have been used in many traditional medicine systems, most notably in the Indian traditional medicine system, known as Ayurveda. The medicinal benefits of spices have only recently been recognized by the scientific community. As a result of the accumulated knowledge on the chemistry of particular active ingredients and their testing in animal studies, scientists have isolated the individual medicinal properties of many herbs & spices. Some health benefits include antidiabetic antioxidant, anti-inflammatory.

THERE’S A REAL INTEREST AROUND HEALTHY EATING AND HEALTHY LIVING IN THE WESTERN WORLD.

The consumption of spices is rising in countries like Australia & the UK because of the associated health benefits.

TURMERIC

TURMERIC is a prime example. Some studies claim a vast array of health benefits of TURMERIC, or one of its components, curcumin. Although other researchers have urged caution on the hype, the claims have fuelled a boom in interest in TURMERIC within the wellness industry.

It has become a very popular product, people are using a lot in their cooking and obviously as well for hot drinks.

But the growth in sales is coming not just from food, but for spices’ alleged health-giving properties. People are self-medicating with TURMERIC for conditions including joint problems.

They’re starting to use TURMERIC as anti-inflammatories, a few years ago you wouldn’t really hear of that. Overall, TURMERIC sales in Western World are growing at nearly 10% a year. The change in consumer behaviour is having an significant effect on the spice industry.

That has an impact on the supply chain itself. If you demand more organic TURMERIC, for example, you have to find more sources of organic spices. That perhaps requires investigating these sources, and farmers transitioning to organic practices.

BASIL

Holy Basil studied for normalizing cortisol levels and “anti-stress effects”, it contains flavonoids orientin, vicenin have been shown to protect chromosomes from free radicals, and volatile oils eugenol, linalool and cineole have anti-bacterial properties – Eugenol blocks cyclooxygenase (COX) giving it analgesic properties

CINNAMON

Has been found to slow gastric emptying reducing rise in post-prandial blood glucose. Recent research showed .83% decrease in A1C in Type 2 DM patients. Has been studied in and found benefit in small trials in Poly Cystic Ovarian Syndrome and boosting cognitive functioning. The volatile oils in Cinnamon show antifungal and antibacterial effects. Used as a “warming” spice with Ginger at the first sign of a respiratory infection, Can lower blood sugar, triglycerides, LDL and total cholesterol. In addition, it is also used by different people of Kashmiri origin, Cinnamon is used for treat infectious diseases. It regarded as a folk remedy for indurations of spleen, breast, uterus, liver and stomach) and tumours especially those of the abdomen, liver and sinews.

CORIANDER

Is originated to a region of southwestern Asia and North Africa and known as Cilantro, Chinese Parsley, Mexican Parsley, Arab Parsley, Dhania and Yuen sai. Traditionally it is used in infection related to digestive problem, respiratory and urinary systems and having stimulant action. The Coriander plant is highly recommended for anxiety and insomnia in Iranian folk medicine, very common in Mexican diet, usually consumed uncooked, the oil of coriander also having an antimicrobial property and as a natural fragrance in perfumery industry. Coriander also called as “Maadnouss” in Morocco and well recommended for urethritis, cystitis, urinary tract infection, urticaria, rash, burns, sore throat, vomiting, indigestion, nosebleed, cough, allergies, hay fever, dizziness and amebic dysentery.

FENUGREEK

Fenugreek is a kind of seed, which are mainly used as kitchen spices in India, commonly known as maithray (Bangla, Gujarati), methi or mithi (Hindi, Nepali, Marathi, Urdu and Sanskrit). In Latin “Fenugreek” or foenum-graecum is known for “Greek hay.” In medicines it is used as an aphrodisiac property, astringent, demulcent action, carminative, stomachic, diuretic, emmenagogue, emollient, expectorant, lactogogue, restorative, and tonic a Tonic . Fenugreek also used for a variety of health situations, including digestive disorders, bronchitis, tuberculosis infection, fevers, sore throats problem, wounds healing, arthritis, abscesses, swollen glands, skin irritations reaction, loss of appetite, ulcers and menopausal symptoms, diabetes, as well as in the treatment of cancerous infection. Leaves infusion is used as a gargle for treatment of mouth ulcers. It also overcomes problem releated to reduce blood sugar level and to lower blood pressure.

GARLIC

Garlic is the oldest remedy used as early as 3000 BC for the treatment of intestinal disorders and is known for its fibrinolytic activity with lowering blood cholesterol. Garlic species mainly refer to the Onion family, Alliaceae. This spice has also been used in folk medicine for diabetes and inflammation treatment. In Nepal, East Asia and the Middle East has been used to treat all manner of illnesses including fevers, diabetes, rheumatism, intestinal worms, colic, flatulence, dysentery, liver disorders, tuberculosis, facial paralysis, high blood pressure and bronchitis In Ayurvedic and Siddha medicine juice of Garlic has been used to alleviate sinus problems. In Unani medicine, an prepared extract by the dried bulb is inhaled to promote abortion or taken to regulate menstruation. Unani physicians has also use Garlic to treat paralysis, forgetfulness, tremor, colic pains, internal ulcers and fevers. Cardiovascular benefits (lowers triglycerides and total cholesterol, lower blood pressure, decreases atherosclerosis). Meta-analysis showed those with highest consumption of garlic had 41% lower risk colon cancer compared to those with lowest intake. Anti-bacterial and anti-viral effects

ROSEMARY

Contains rosemarinic acid, carsonic acid, and carnosol a special blend of antioxidants making rosemary a more potent antioxidant than BHA/BHT (manmade antioxidants). When used as marinade or added to meats when grilling up to a 61% decrease in heterocyclic amines (HCA. It has been shown to lower cortisol levels when inhaled and has been shown to improve memory. May reduce the risk of some cancers and can help prevent damage to the blood vessels that raise heart attack risk.

POPPY SEED

Poppy seed is an oilseed obtained from the Poppy The tiny kidney-shaped seeds have been harvested from dried seed pods by various civilizations for thousands of years. It is still widely used in many countries, especially in Central Europe, where it is legally grown and sold in shops. The seeds are used, whole or ground, as an ingredient in many foods-especially in pastry and bread, and they are pressed to yield Poppy seed oil. In a 100 gram amount, Poppy seeds provide 525 Calories and are a rich source of thiamin, folate, and several essential minerals, including calcium, iron, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus and zinc (table). Poppy seeds are composed of 6% water, 28% carbohydrates, 42% fat, and 21% protein (table). In Indian cuisine white Poppy seeds are added for thickness, texture and also give added flavour to the recipe. Commonly used in the preparation of Korma, ground Poppy seeds, along with coconut and other spices, are combined as a paste, to be added at the last stage of cooking. It is quite hard to grind them when raw, so they are normally toasted/broiled and water added when grinding to get the right consistency In Indian traditional medicine Ayurveda soaked Poppy seeds are ground into a fine paste with milk and applied on the skin as a moisturizer. Poppy seeds are pressed to form Poppy seed oil, valuable commercial oil that has multiple culinary, industrial, and medicinal uses.

PAPRIKA

Contains capsaicin, which may have anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects.

GINGER

It is also known as aadu in Gujarati, shunti in Kannada, allam in Telugu, zanjabil in Arabic, inji in Tamil and Malayalam and adrak in Hindi and Urdu. Ginger is commonly used as a spice in cooking throughout the world and especially used in kitchen. The ginger rhizome mainly used in Ayurvedic and traditional Chinese medicine to overcome a vast variety of gastrointestinal disorders, mainly nausea and vomiting associated with motion sickness and pregnancy, abdominal spasm, as well as respiratory and rheumatic disorders. Ginger is widely used for dyspepsia, flatulence, abdominal discomfort and nausea. It also used as astringent, an agent that causes shrinkage of mucous membranes or exposed tissues and that is often used internally to check discharge of blood serum or mucous secretions .Studied extensively for GI complaints (motion sickness, nausea & vomiting from multiple causes). Has been found beneficial in small trials for osteoarthritis and migraine. Warming and used in respiratory infections. May also relieve pain and swelling associated with arthritis.

THYME

Can reduce swelling and inflammation and has been known to strengthen the body’s immune system.

CHILLI

Red Chilli is the commonly used spice bins our daily life. Chilli, plant specify genus Capsicum, which among the most popular consumed spices all around the worldwide. This name, Chile, or Chilli arises from Nahuatl Chīlli via the Spanish word Chile. Chilli has one another application used as an alternative medicine for the inflammation treatment, diabetes problem, and low back pain and also uses in to treat acute tonsillitis. capsicum plaster, that contains finely divided powdered capsicum and capsicum tincture solution, has been used in Korean hand acupuncture to reduce postoperative nausea, sore throat problem, vomiting.

AJWAIN

From theFamily Apiaceae or Umbelliferae, It originated in India. Both the leaves and the seed-like fruit, which are often mistakenly called seeds, of the plant are consumed by humans. The name “bishop’s weed” also is a common name for other plants. The “seed” i.e., the fruit, is often confused with Lovage “seed”. Ajwain’s small, oval-shaped, seed-like fruits are pale brown schizocarps, which resemble the seeds of other plants in the Apiaceae family such as Caraway, Cumin and Fennel. They have a bitter and pungent taste, with a flavour similar to Anise and Oregano. They smell almost exactly like Thyme because they also contain thymol, but they are more aromatic and less subtle in taste, as well as being somewhat bitter and pungent. Even a small number of fruits tend to dominate the flavour of a dish. Ajwain is used in traditional Ayurvedic medicine primarily for stomach disorders such as indigestion, flatulence diarrhea and colic. In Siddha medicine, it is used as a cleanser, detox, and antacid. In general, the crushed fruits are applied externally as a poultice.

CAYENNE PEPPER

Contains capsaicin and can help relieve pain. May also have a positive effect on cholesterol, and studies show cayenne pepper contributes to lower blood pressure.

CARDAMOM

In Ayurveda it is well known for carminative property, diuretic action, cough relive, colds and cardiac stimulation. Traditionally it used against kidney and urinary disorders and also having gastrointestinal protective property. Cardamom oil having anti-inflammatory and antibacterial property. In India, Green Cardamom have widely used to treat infections against teeth and gums, to overcome treat throat trouble, congestion of the lungs and pulmonary tuberculosis, asthma, heart disease, inflammation of the eyelids and digestive disorders. Nasal preparation for cold is prepared by mixing Cardamom with Neem and Camphor. Cardamom infusion is used as a gargle to relieve sore throats. It is reported as an antidote for both snake and scorpion venom and also used for food poisoning. In Chinese Medicine it is also traditionally used to treat stomach-ache disorders, constipation problems, dysentery in children, and other digestion related problems. The pods of Cardamom, also effective when it is used as fried and mixed with mastic and milk, are effective against bladder problems. Cardamom seeds are well known to be an aphrodisiac property.

ENJOY TASTES FROM AROUND THE WORLD

Many ethnic cuisines are distinguished by the spices used in preparing them. If you’re trying to make a Indian dish, try using the spices found in the INDIAN GARAM MASALA section below to create those traditional Indian food flavours you love. If you’re following a recipe for an ethnic dish and the result is too bland, try adding in more of the spices in the respective section to achieve your desired taste.

WITH THESE SPICE COMBINATIONS, YOU’LL BE WHIPPING UP DISHES FROM ALL OVER THE WORLD!

NORTH AFRICAN RAS EL-HANOUT

The name means “head of the shop,” a shorthand for the best spices the shop has for sale. Some mixes, like this one, do not have a specific recipe, so the RAS EL-HANOUT that you buy at one shop will differ from another. Some say that it must contain 12 spices, but which 12 spices is a matter of debate, and differs from region to region

The standard components are Pimento, Ginger, Chilli, Coriander, Turmeric, Mace, Nutmeg, Clove, Cumin, Cardamom, hot Paprika, sweet Paprika, Pepper and Fenugreek. But in case that’s not enough, there are some even more exotic components, such as Chufa, Orris root, Galangal, Monk’s Pepper, Cubebs, dried Rosebud, Ash berries, and even Cantharides (an aphrodisiac which is now banned in Morocco) I’d heard of almost none of those, but I’ll put RAS EL-HANOUT in just about anything, from meat to fish to rice. So, bring on more Cubebs!

ISRAELI ZA’ATAR

A herb, more than a SPICEBLEND, this features Oregano (which scholars have linked to the Biblical herb, hyssop), Basil, Thyme and Savory, with the addition of Sesame Seeds, dried Sumac and Salt. Now trending all over Australia’s trendy eateries, it can be used for cooking or as a dip,a toasted flatbread dipped in olive oil first, then ZA’ATAR is pretty killer.

KUWAITI BAHARAT

BAHARAT just means “spices” in Arabic, and so this is a sort of shorthand for any Middle Eastern SPICEBLEND, but it normally features Pimento, Black Pepper, Cardamom, Cloves, Coriander, Cassia, Cumin, Nutmeg and Paprika. The Turkish version, however, stands out, since it also includes Mint, and is particularly nice on roasted meat with a yogurt sauce , as we all know mint and yogurt are a heavenly pairing. In Saudi Arabia you might find a version with added Loomi (dried Black Lime).

SAUDI ARABIAN KABSA

A relatively simple SPICEBLEND ideal for fish, which includes Turmeric, Coriander, Pepper, Black Cardamom, Ginger and Fennel.

CHINESE FIVE SPICE

Fennel, Sichuan Pepper, Chinese Cinnamon, Clove and Star anise are the big five and immediately make your kitchen smell like the local Chinese restaurant. If you have a gas stovetop, a wok and Sesame Oil, then you can reproduce basic Chinese food at home thanks to this SPICEBLEND.

The core of Ethiopian and Eritrean cuisine is a SPICEBLEND of Chili, Garlic, Ginger, Basil … and then it gets exotic. How about some Korarima, Rue, Ajwain, Nigella and Fenugreek. If you are fresh out of those in your cupboard, Just grab some SHASHEMANE ETHIOPIAN BERBERE instead!

MAGHREBIAN HARISSA

Harissa, mostly derived from a cluster of Chillies (roasted Red Cayennes, Tunisian Bakloutis and Serranos), plus Garlic, Coriander and Caraway, it can be dried and powdered or a wet paste. Along Africa’s Mediterranean coast and throughout the Levant, you’ll find HARISSA used as to add smoke and spice to whatever’s cooking, whether as a sauce, dip, crust or marinade.

INDIAN GARAM MASALA

Throughout India and Pakistan, you’ll find GARAM MASALA SPICEBLENDS, the quickest route to bold subcontinent flavours. GARAM means “heat,” not in the spicy sense, but spices were believed to heat the body, providing a sort of fuel that unspiced food cannot provide. Black and White Pepper, Nutmeg, Mace, Cinnamon, Clove, Bay Leaves, Cumin, and Black and Green Cardamom are the staples, though if you happen to have asafetida in the house, I know I do at times, then you can add that, too.

SO GET OFF YOUR BUTT & EXPERIENCE NEW FLAVOURS WITH SPICE BLENDS

While you can now recreate each of these SPICE BLENDS on your own, sometimes it’s nice to have the masters make some SPICE BLENDS for you. I recommend picking 2 or 3 depending on your favourite ethnic cuisines.